Impressionism, a Rebirth

Among artists renowned for their use of pastel, impressionists are frequently included. This handy material –that allows artists to work swiftly and in the open air- is truly compatible with their aesthetic. Nevertheless, the Impressionists who were most passionate about pastel have a true predilection for the representation of the human figure.

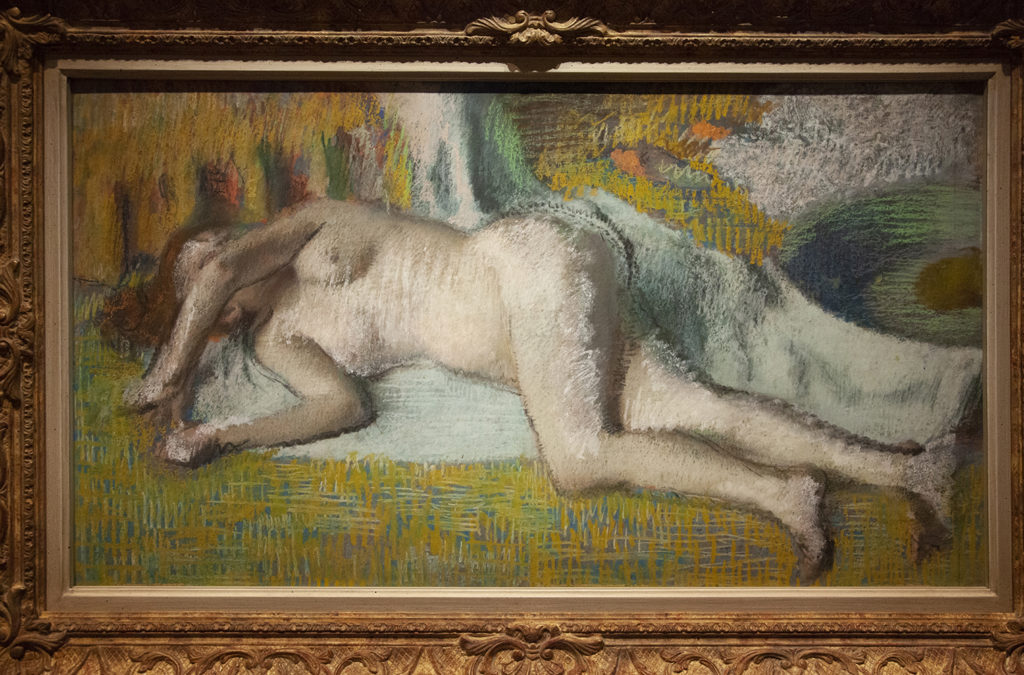

Edgar Degas 1834-1917, “After the Bath”, 1893, ©photo by Bogra art studio, 2019

Edgar Degas 1834-1917, “After the Bath” detail, 1893, ©photo by Bogra art studio, 2019

Edgar Degas 1834-1917, “After the Bath” detail, 1893, ©photo by Bogra art studio, 2019

Such is the case with an artist who maintained a tangential relationship with this trend: Giuseppe De Nittis, whose elegant scenes bathed by the light of a sunny garden or under the grey sky of an autumn park are very successful and sweep with all the honors under the noses of his impressionists’ friends.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917) “Unhappy Nelly”, 1885, ©photo by Bogra art studio, 2019

Edgar Dégas also explores modern life (coffee-theatre scenes, ballets in the Opera, women ironing, etc…) but without knowing the same success.

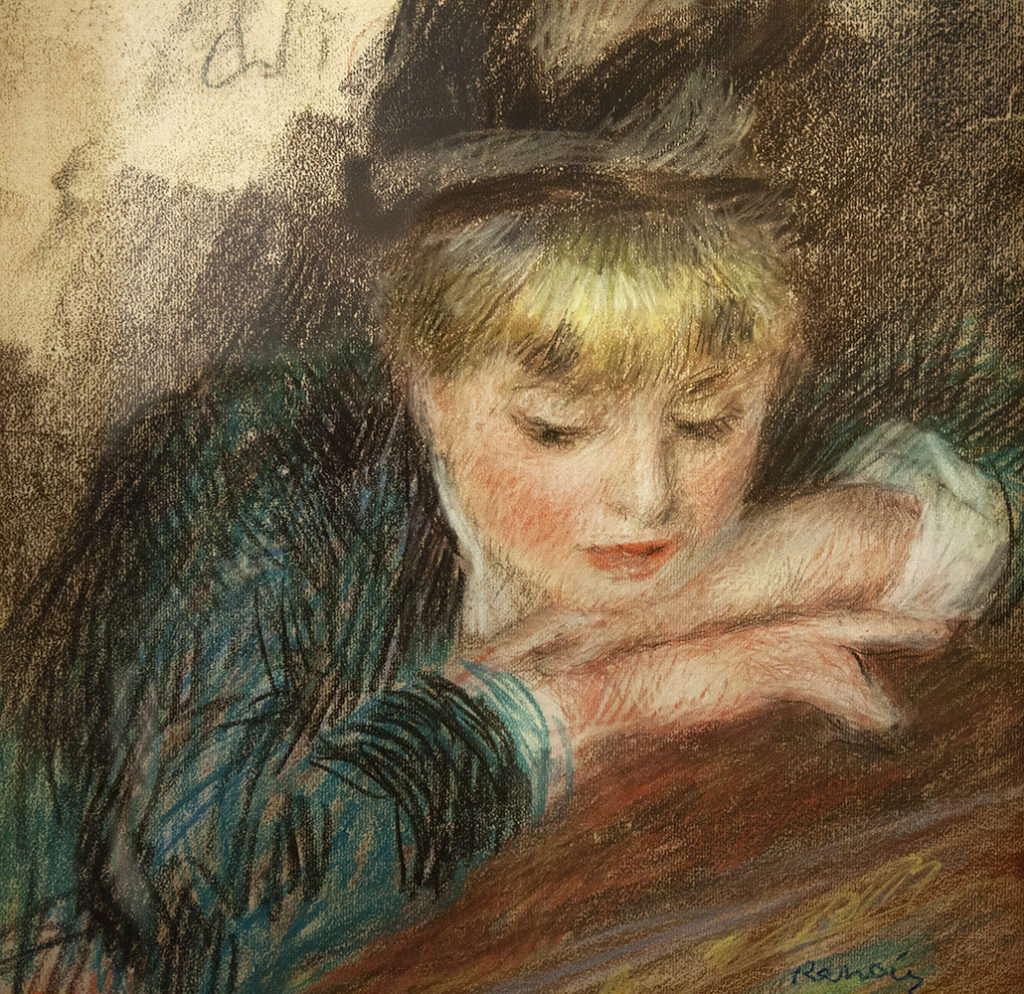

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), “Child with an Apple or Gabrielle, Jean Renoir and a Little Girl”, ©photo by Bogra art studio, 2019

“Child with an Apple or Gabrielle, Jean Renoir and a Little Girl” detail, 1895, ©photo by Bogra

Wounded in the most vivid he would respond to his Italian colleague, who had already passed away at the time, with his famous series of female nudes, whose triviality opposes the focus on elegance that granted De Nittis so much praise. This usage of pastel is much more defiant and perfectly illustrates Dega´s famous adagio: “Grace is in common things”

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), “The Theater Box” 1879, ©photo by Bogra art studio

On his part, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, whose work is indefectibly linked to the female figure, take the pastels to run with agile, effigies full of charm. Renoir, whose passion for the eighteenth century is notorious, rediscovers with this medium the joy of his illustrious precursors, who, like him, handled the pastels with apparent ease.

Henry Tonks (1862-1937), “The Toilet”, 1914, ©photo by Bogra 2019

Henry Tonks (1862-1937), “The Toilet” detail, 1914, ©photo by Bogra 2019

The 20th Century: From symbol to Gesture

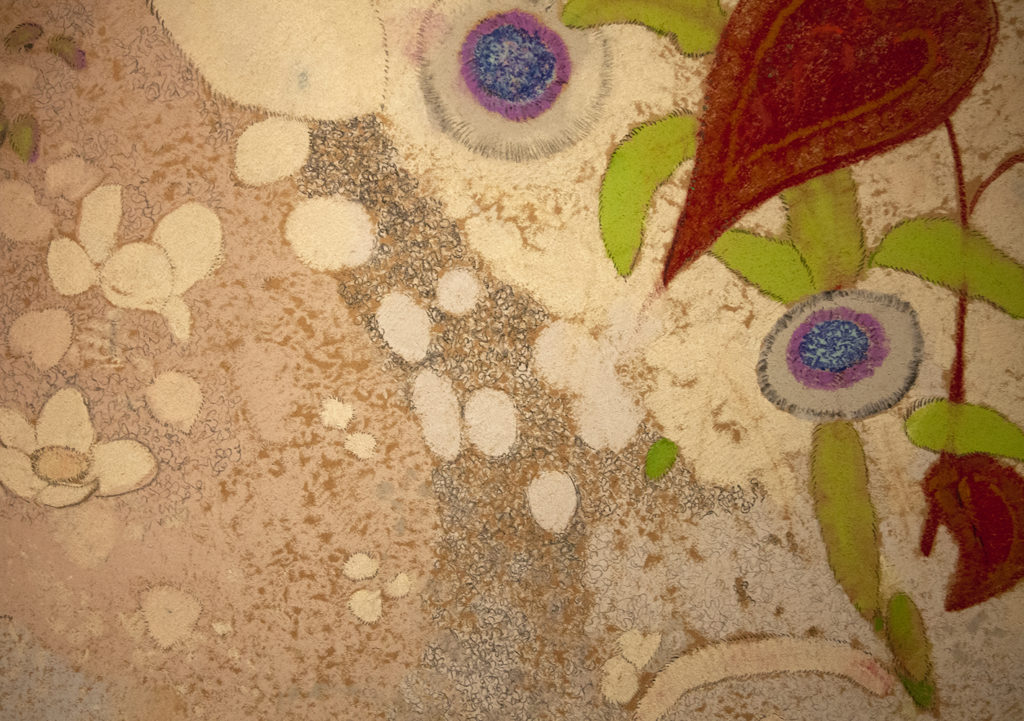

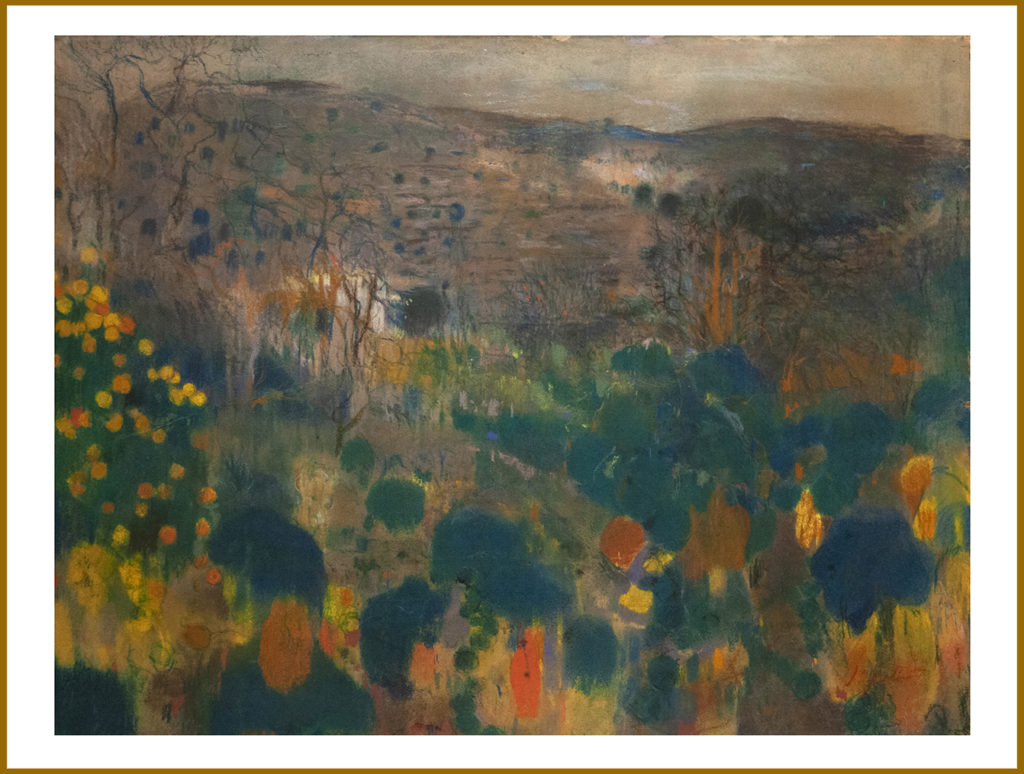

The use of pastel in the early 20th cannot be understood without the mastery of Odilon Redon nor without the diffuse spirituality of late Symbolism, that stems from parts of the language used by the Avant-garde: Joseph Stella, the first Theo Van Doesburg, Otto Freundlich or Joaquim Mir demonstrate how the transnational language of the turn of the century settles within and foreshadow abstraction.

Odilon Redon (1840-1916) “Flowers”, 1909, photo by ©Bogra art studio, 2019

Odilon Redon (1840-1916) “Flowers”, detail, 1909, ©Bogra art studio, 2019

“Pastel painting exhibition”, “Touching Color”, The renewal of Pastel, photo by ©photo by Bogra

These creators distanced themselves from the debate over hierarchy of techniques: pastel was not imbued with greater or lesser nobility; it simply facilitates the enunciation of a particular message.

Joaquim Mir (1873-1940), “Landscape” 1900-1903, photo by ©photo by Bogra art studio, 2019

This is the role it takes in the Works of the more classical Pablo Picasso, such a Study of hands, or in The reaper by Pablo Gargallo, where he supports skin-like textures and provides sweetness and chromatic richness that is recovered after cubism.

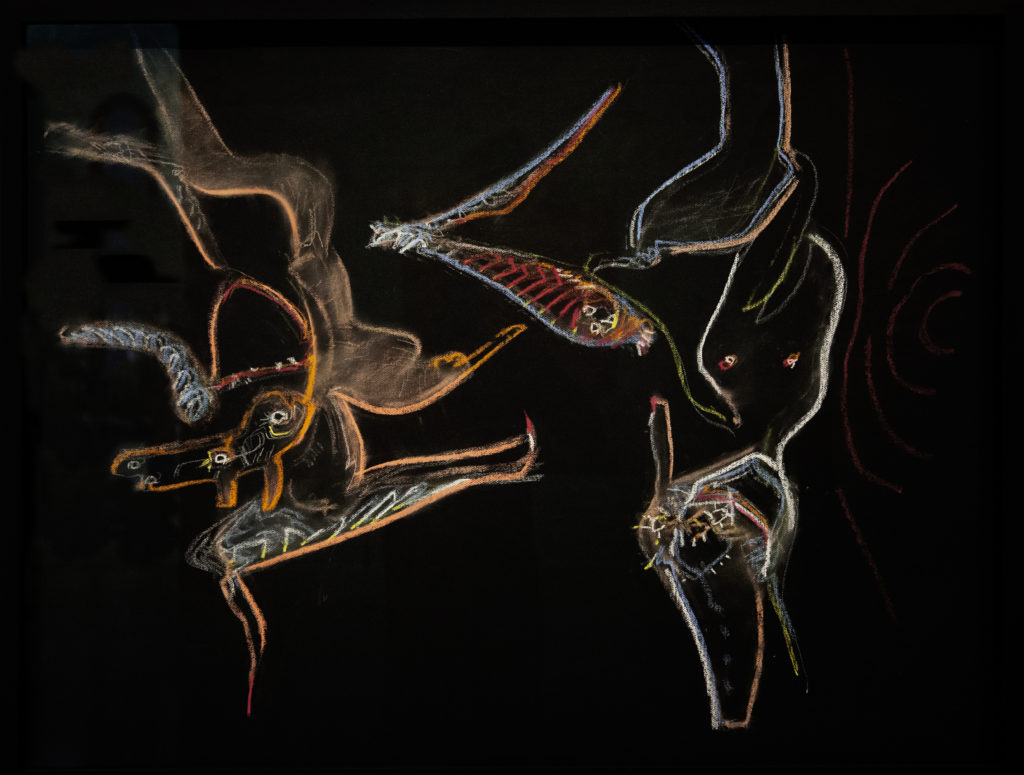

Joan Miró (1893-1983) “Figure” 1934, The renewal of Pastel, ©photo by Bogra art studio, 2019

In an unbiased way, Joan Miró also resorts to pastel: decades after the juvenile Bellver Forest, he returns to the medium in a fundamental chapter of savage paintings from 1934, countering the elegant pastel portraits of the previous century.

Roberto Matta (1911-2002) “L`Opresavio y L´Opresente”, 1986, photo ©Bogra art studio, 2019

While fellow artists, such as Roberto Matta or André Masson, recall how surrealism found the pastel to be one of the methods by which to transfer the relationship between the hand and the pencil, characteristic of automatic writing, into painting.

Marie Blanchard (1881-1932) “La Bretonne”, 1928, photo by ©Bogra art studio, 2019

Amédée Ozenfant (1886-1966) “Still Life”, 1925, photo ©Bogra art studio, 2019

Amédée Ozenfant (1886-1966) “Still Life in an Oval”, 1928, photo ©Bogra art studio, 2019

A link that has its final accent in the work of Hans Hartung, who reactive pastel as a type of painting where previously rehearsed personal spellings reverts the idea of automatisms through the ritual of repetition. Hartung exemplifies the way in which 20thcentury artists touched color with iconoclastic and multi-formed gestures of their hands until they are able to expand the frontiers of pastel, liberated from prejudice, emancipated from its own history.

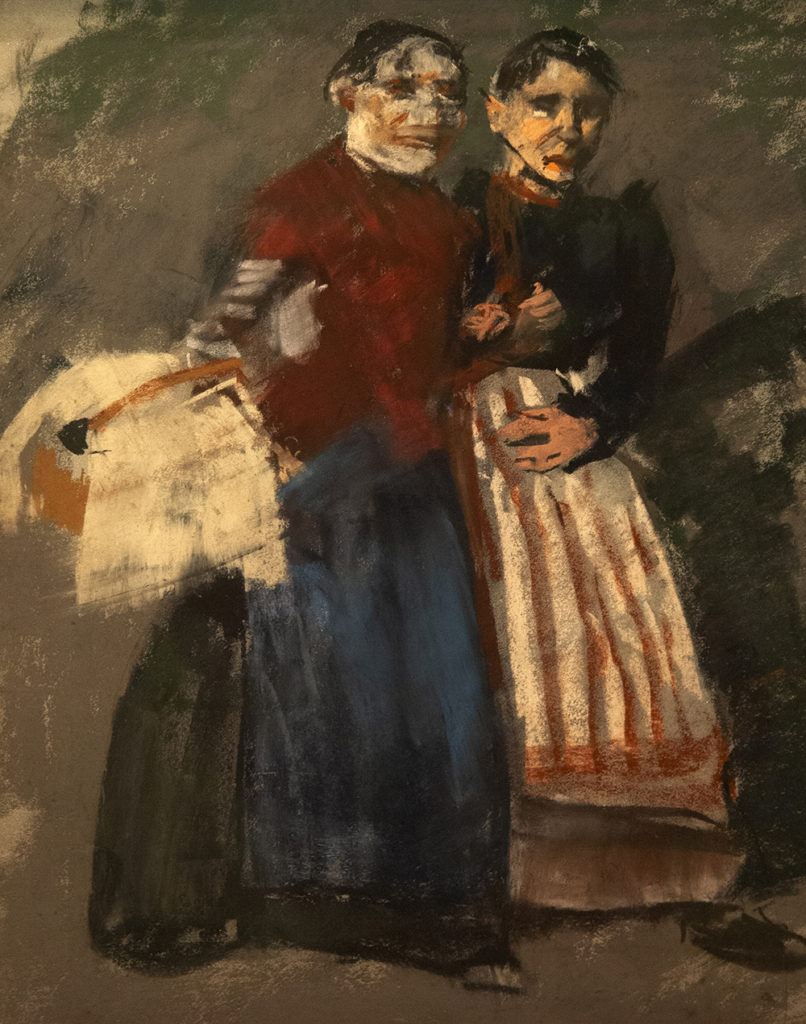

George Hendrik Breitner, “Two Amsterdam Household Maids”, 1892, photo by ©Bogra , 2019